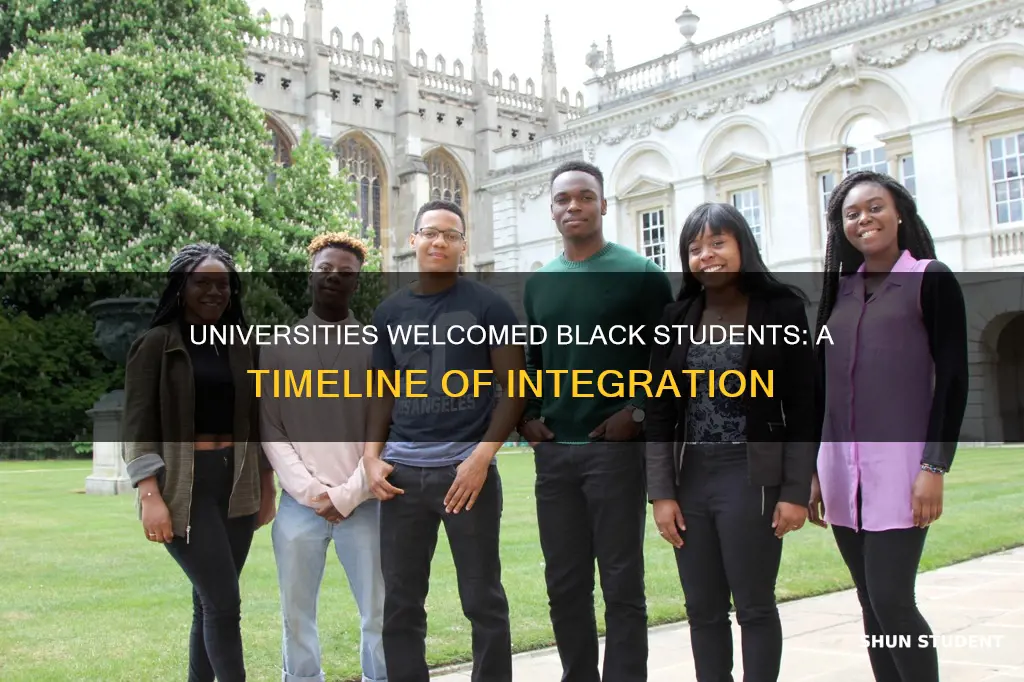

The history of the admission of Black students into universities in the United States is a complex and often painful one. While there were a handful of Black graduates from American universities in the early 19th century, such as Alexander Lucius Twilight, who graduated from Middlebury College in 1823, and W.E.B. Du Bois, who earned a Ph.D. from Harvard University, the majority of universities were unwelcoming to Black students until the mid-20th century. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 finally opened colleges and universities to all students, but it was not until the Supreme Court rulings in Sweatt v. Painter (1950) and Brown v. Board of Education (1954) that racial segregation in public education facilities was outlawed. Even after these rulings, Black students often faced protests, riots, and discrimination when attempting to enroll in predominantly white universities. The first Black students at the University of Georgia in 1961, for example, were met with riots and protests from white students. In the same year, James Meredith became the first Black student at the University of Mississippi, and his entry was only achieved through the intervention of Attorney General Robert Kennedy and the deployment of military police and National Guard troops by President Kennedy.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Year when universities were allowed to enrol black students | 1828, 1865, 1889, 1948, 1950, 1951, 1952, 1961, 1962, 1964 |

| First Black student admitted | Theodore Sedgwick Wright, Fred Patterson, Silas Hunt, Gene Mitchell Gray, Gregory Swanson, N/A, N/A, Charlayne Hunter, James Meredith, N/A |

| University | Princeton Theological Seminary, Ohio State University, University of Arkansas, University of Tennessee, University of Virginia School of Law, N/A, N/A, University of Georgia, University of Mississippi, N/A |

What You'll Learn

- The Civil Rights Act of 1964 opened colleges and universities to all students

- HBCUs were founded to educate Black students

- In 1890, the Second Morrill Act required segregated Southern states to provide African Americans with public higher education

- In 1950, Kentucky's Day Law was amended to allow Black and White students to be educated together

- In 1961, the University of Georgia's first Black students were greeted with riots and protests by White students

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 opened colleges and universities to all students

For a long time, colleges and universities in the United States did not allow Black students to enrol. In the 19th century, most colleges and universities prohibited Black students from attending. During this period, Black students were unwelcome at existing public and private institutions of higher education, and those that did admit Black students were rare.

The original purpose of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) was to provide education for Black Americans at a time when most colleges and universities did not allow them to enrol. HBCUs were established in the United States early in the 19th century, with the majority originating from 1865-1900. The first HBCU in the Southern United States was Atlanta University, founded on 19 September 1865. HBCUs were often founded by religious organisations, with the American Missionary Association playing a significant role in their financing.

In the years following the Civil Rights Act, there was a push for predominantly white institutions to increase their enrolment of Black students. This push came from both government mandates and student activism. The assassination of Dr Martin Luther King in 1968 further catalysed this effort, with predominantly white institutions committed to educating Black students to an unprecedented degree. As a result, the number of Black students enrolled in U.S. colleges and universities increased significantly, contributing to a reduction in poverty among African Americans.

Expansive Student Body at the University of Washington

You may want to see also

HBCUs were founded to educate Black students

Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) were founded to provide Black students with educational opportunities that were otherwise unavailable to them due to segregation and discriminatory laws. The original purpose of HBCUs was to educate African Americans, and they played a crucial role in the post-Civil War era, when most colleges and universities in the United States prohibited Black students from enrolling.

During the Reconstruction era, most HBCUs were founded by Protestant religious organizations, with support from organizations like the American Missionary Association and financing from the Freedmen's Bureau. Atlanta University, now Clark Atlanta University, was the first HBCU in the Southern United States, founded on September 19, 1865. It was also the first graduate institution to award degrees to African Americans.

For a century after the abolition of slavery in 1865, almost all colleges and universities in the Southern United States prohibited African Americans from attending due to Jim Crow laws. Even before this, Black students faced significant barriers to accessing higher education. While some attended predominantly white institutions, they often faced racism and discrimination from faculty, staff, and fellow students.

The Second Morrill Act of 1890 required segregated Southern states to provide African Americans with public higher education to receive the Act's benefits. However, it wasn't until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that colleges and universities were officially opened to all students, regardless of race. Even after this, HBCUs continued to play a vital role in providing educational access to Black students.

In the late 20th century, HBCUs saw a decline in Black student enrollment as predominantly white institutions (PWIs) began to actively recruit and admit more Black students. Despite this shift, HBCUs remain important centers of education and community leadership development for Black students, with a unique history and mission to educate and empower African Americans.

University Students and NHS: Free Prescriptions Explained

You may want to see also

In 1890, the Second Morrill Act required segregated Southern states to provide African Americans with public higher education

In 1890, the Second Morrill Act required segregated Southern states to establish separate Land-grant Institutions for Black students or demonstrate that admission to the 1862 Land-grant colleges was not restricted based on race. Sponsored by Senator Justin Morrill of Vermont, the Act was signed into law by President Benjamin Harrison on August 30, 1890. The Second Morrill Act aimed to expand educational opportunities for people of colour, specifically in agriculture and mechanical arts.

Prior to the Second Morrill Act, people of colour were often excluded from educational opportunities at the Land-grant Universities (LGUs) established by the first Morrill Act of 1862. The Act of 1890 granted money, instead of land, and resulted in the designation of a set of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) as Land-grant Universities. These colleges began receiving federal funds to support teaching, research and extension services intended to serve underserved communities. The Second Morrill Act facilitated segregated education, but it also provided higher educational opportunities for African Americans who were otherwise excluded from higher education due to Jim Crow laws in the South.

The Morrill Land-Grant Acts are United States statutes that allowed for the creation of land-grant colleges in U.S. states using the proceeds from sales of federally owned land. The Morrill Act of 1862 was enacted during the American Civil War, and the Second Morrill Act of 1890 expanded this model to include the former Confederate states. The 1862 Act was eventually extended to every state and territory, and the management of the scrip yielded one-third of the total grant revenues generated by all the states.

The Second Morrill Act led to the establishment of several HBCUs, and today, these institutions continue to receive support from various programs. The USDA's National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) provides funding and support for institutional capacity building, research, scholarships, and more. The 1890 Facilities Grant Program supports the acquisition and improvement of agricultural and food sciences facilities and equipment, including libraries. The Evans-Allen Act of 1977 provided capacity funding for food and agricultural research at the 1890 Land-grants, similar to the funding provided to the 1862 Land-grants under the Hatch Act of 1887.

Texas State University: Student Review Process Explained

You may want to see also

In 1950, Kentucky's Day Law was amended to allow Black and White students to be educated together

The history of Black students' admission into universities in the United States has been a gradual process, with various milestones contributing to increased access and racial integration. One significant event occurred in 1950 when Kentucky's Day Law was amended, marking a pivotal step towards racial equality in education.

The Day Law and Its Impact:

The Day Law, introduced in 1904 by Kentucky Representative Carl Day, was a segregationist bill that prohibited Black and White students from attending the same school. Formally titled "An Act to Prohibit White and Colored Persons from Attending the Same School," the law enforced strict racial segregation in Kentucky's educational institutions. This law particularly targeted Berea College, the only integrated college in Kentucky at the time, which was fined $1,000 for violating the Day Law. The law also prohibited schools from operating separate Black and White branches within 25 miles of each other, further limiting educational opportunities for Black students.

Amending the Day Law in 1950:

In 1950, a significant shift occurred when Kentucky's Day Law was amended to allow Black and White students to be educated together. This amendment specifically applied to students above the high school level. As a result, Berea College became the first institution in Kentucky to readmit Black students, marking a crucial step towards racial integration in the state's higher education system. The amendment to the Day Law reflected a broader push for racial equality and access to educational opportunities across the United States.

Broader Context of Racial Integration in Education:

The amendment to the Day Law in 1950 was part of a broader movement towards racial integration and equality in education. During the Reconstruction era following the American Civil War, most historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) were founded by religious organizations to provide educational opportunities for African Americans. The passage of the Second Morrill Act in 1890 required segregated Southern states to provide public higher education to African Americans, even as many other colleges and universities prohibited Black students' enrollment due to Jim Crow laws.

The civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s further advanced racial integration in higher education. Landmark Supreme Court cases, such as Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, declared segregation in public schools unconstitutional, directly impacting the Day Law's legality. The enactment of civil rights laws in the 1960s also led to affirmative action policies, with educational institutions receiving federal funding increasing their racial diversity. Despite resistance and riots at some universities, Black students gradually gained admission to previously all-White institutions, marking a significant shift towards racial equality in higher education.

Full Scholarships for International Students at Arizona State University?

You may want to see also

In 1961, the University of Georgia's first Black students were greeted with riots and protests by White students

For a century after the abolition of American slavery in 1865, almost all colleges and universities in the Southern United States prohibited Black students from attending, as required by Jim Crow laws. During the Reconstruction era, most historically Black colleges were founded by Protestant religious organisations. This changed in 1890 with the U.S. Congress' passage of the Second Morrill Act, which required segregated Southern states to provide African Americans with public higher-education schools in order to receive the Act's benefits.

In the 1950s, some universities began to allow Black students to enrol. In 1950, Berea College became the first college in Kentucky to readmit Black students. That same year, the University of Virginia School of Law admitted Gregory Swanson, its first Black student, following a ruling by the U.S. Court of Appeals. In 1951, the University of North Carolina School of Law admitted its first Black student, and Princeton University awarded its first honorary degree to a Black person, Ralph Bunche. In 1952, the University of Tennessee admitted its first Black student.

Despite these steps forward, racism and segregation still plagued the education system in the early 1960s. In 1961, the University of Georgia's first Black students, Charlayne Hunter and Hamilton Holmes, were greeted with riots and protests by White students. On January 9, 1961, Hunter and Holmes arrived on campus to register for classes, following a lengthy legal battle to integrate the university. They were met by a mob of nearly 100 White students, local residents, and Ku Klux Klan members, who threw bricks and bottles, set fires, and yelled racial slurs. The riot was eventually quelled by campus officers, city police, and local firefighters.

The desegregation of the University of Georgia was a significant step toward integrating colleges and universities in the Deep South. It directly challenged Georgia legislation that terminated funding for state-run, integrated universities, and the school administration successfully fought to remain open and continue the integration process.

Boston University's International Student Population: A Comprehensive Overview

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The University of Texas allowed Black students in 1950 when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that UT was required to desegregate its graduate programs.

The University of Georgia allowed Black students in 1961 when Charlayne Hunter and Hamilton Holmes enrolled as students.

The University of Mississippi allowed Black students in 1962 when James Meredith became the school's first Black student.

The University of North Carolina School of Law allowed Black students in 1951.

The University of Tennessee allowed Black students in 1952.